Teens’ Self-Reported Expectations and Intentions for Marriage, Cohabitation, and Childbearing

Katherine Graham, Karen Benjamin Guzzo, and Wendy D. Manning

Overview

Families in the United States are changing. People are waiting longer to marry and, in some cases, not marrying at all. Cohabitation is now common in young adulthood and most people have lived with someone in a cohabiting union—usually their eventual spouse—prior to marriage. Additionally, birth rates have fallen to record lows in recent years.

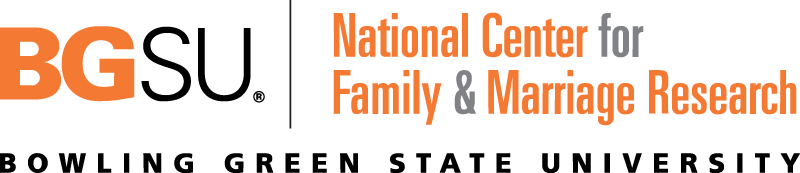

While there are many reasons for such changes, they do not appear to reflect a lack of interest in marriage or family formation among young people. As shown in Figure 1, recent nationally representative data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) demonstrate that the vast majority of U.S. teens ages 15 to 19 expect or intend to cohabit, marry, and have children in the future.

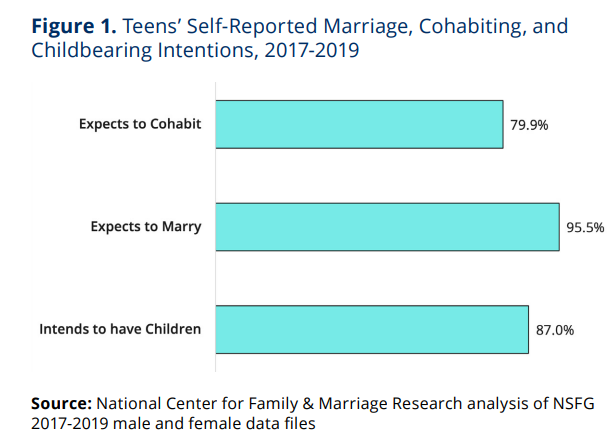

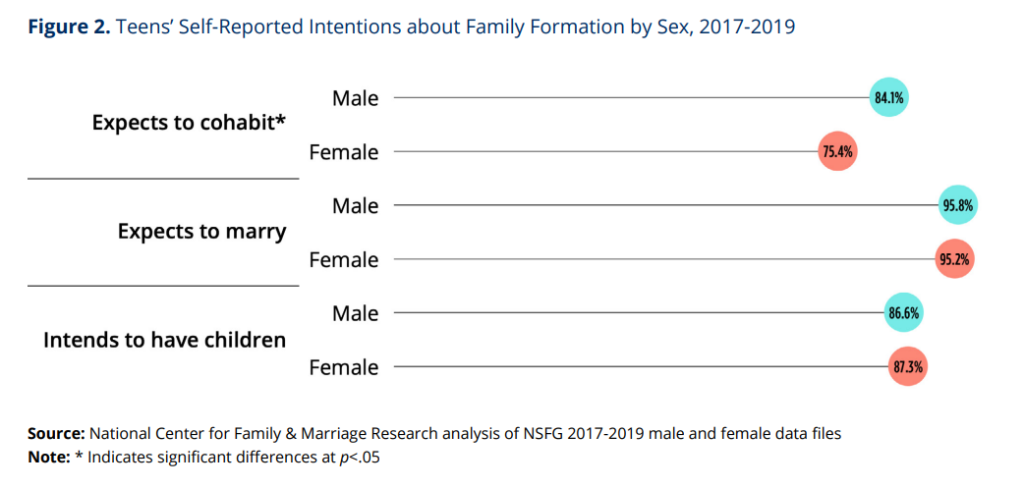

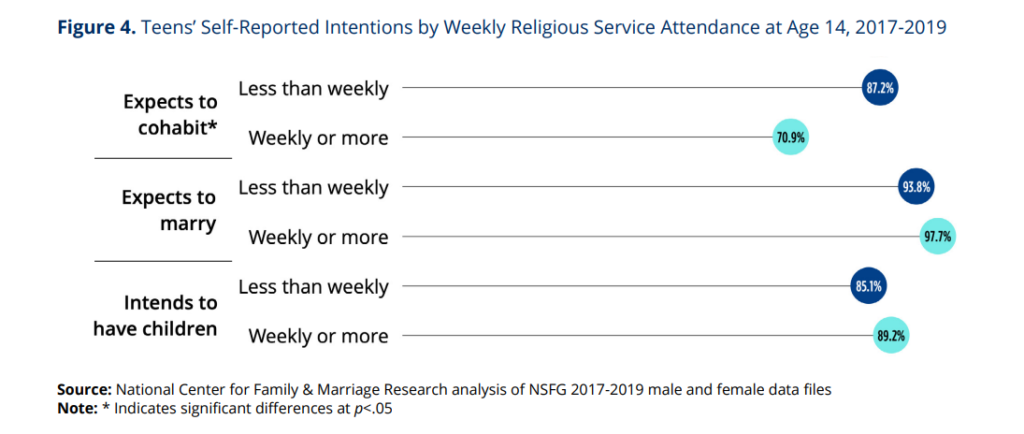

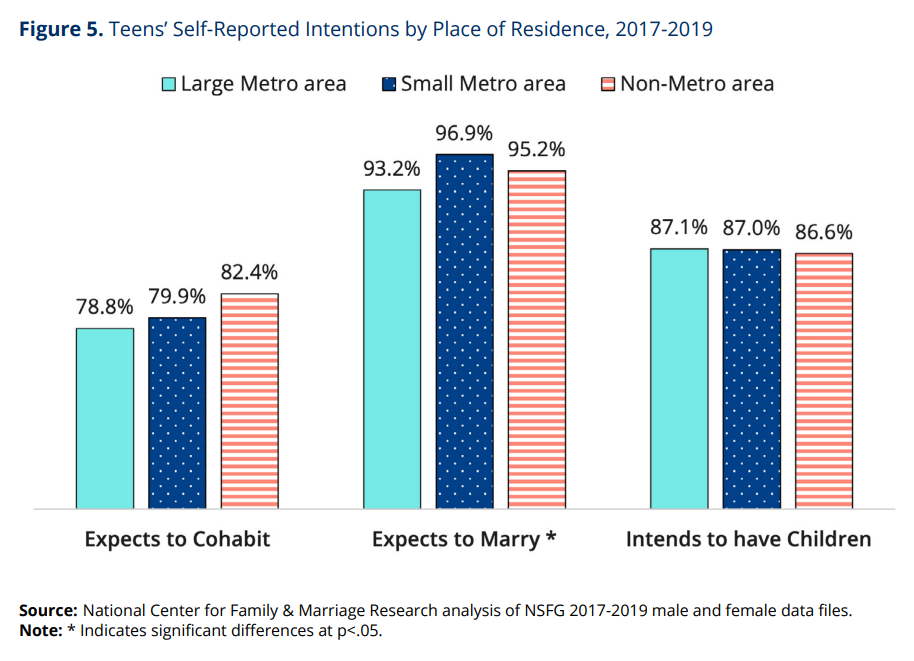

Prior research has found that individual expectations about family behaviors differ across social and demographic characteristics such as gender, family structure, religiosity, and metropolitan area. However, although the share of teens who anticipate cohabitation, marriage, and parenthood varies across these social and demographic characteristics—as we show in figures 2 through 5—the differences are relatively minor.

For instance, Figure 2 illustrates that almost all teenage boys and girlsa reported that they expect to get married someday (96% and 95%, respectively) and intend to have children (about 87%). However, while most teen boys and girls expected to cohabit at some point in the future, this share is significantly higher

among boys (84%) than among girls (75%).

Most teens, regardless of their family structure at age 14, reported that they expect to cohabit, marry, or have children at some point in the future (Figure 3). The share of teens who expected to marry was somewhat lower (91%) for teens who lived in ‘other’ parental living situations (e.g., single-parent families, grandparent families, etc.) than for teens who lived with both biological parents (97%) or with a biological mother and stepfather (96%).

Teens’ marriage and cohabitation expectations also differed by attendance at religious services (Figure 4). A greater share of teens who attended religious services at least weekly reported expecting to marry (98%) at higher rates than those who attended less frequently (94%), and fewer expected to cohabit (71% and 87%, respectively).

Teens’ expectations about marriage varied slightly by whether they lived in a large or small metropolitan area, or in a non-metropolitan areab (Figure 5). Among those in large metropolitan areas, 93 percent expected to marry compared to 97 percent who lived in small metropolitan areas and 95 percent in non-metropolitan areas. There were no significant differences in expectations about cohabitation or childbearing by where one lived.

Conclusion

Even with rapid changes in family behaviors in the United States, the vast majority of teens reported expectations of forming coresidential unions and having children at some point in the future. Even when there were differences in expectations and intentions between teen boys and teen girls—or by family structure, religiosity, and one’s place of residence—these differences were fairly small. However, it remains to be seen whether teens will be able to fulfill their goals. Larger economic and structural factors—such as increasing housing costs, unstable employment, changing gender norms, and education inequality—may impact young people’s ability to achieve their family goals or alter their family formation expectations as they age, as could how they perceive their futures in light of structural challenges and changing norms.

Footnotes

a The NSFG has separate analytic files for females and males. The survey does not include any measures on gender identity or whether someone is transgender, so we use male/boy to refer to individuals included in the male analytic file and female/girl to refer to individuals included in the female analytic file.

b Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) have at least one urbanized area with a population of 50,000 or more, plus adjacent territory that has a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured by commuting ties. The National Survey of Family Growth defines a large metropolitan area as the principal city of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), a small metro area as the other areas (not the principal city) of a MSA, and non-metro areas as those areas not in an MSA.

Methods

Our analyses use the 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Only adolescents ages 15-19 who had never cohabited, married, or had children were included in the analyses. The final sample consisted of 2,002 teens (1,032 males and 970 females). All estimates were weighted to account for survey design, and chi-square tests were used to test for significant differences in expectations/intentions across the categories of the social and demographic indicators.

Expectations of marriage are based on answers to the question, “What is the chance you will get married someday?” Expectations of cohabitation are based on answers to the questions, “Do you think that you will live together with your future husband/wife before getting married?” (if affirmative response to the marriage question) and “What is the chance that you will ever live with a man/woman to whom you are not married?” (if negative response to the marriage question). The response categories for the marriage and cohabitation questions are definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, and definitely no; our analyses show only the share who responded “definitely” or “probably” yes to cohabitation and marriage.

Childbearing intentions are based on answers to the question, “Looking to the future, do you intend to have a baby at some time?” The response categories included “yes” or “no,” and we show only the share reporting yes.

Data Source

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth Public-Use Data and Documentation. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/index.htm

Suggested Citation

Graham, K., Guzzo, K.B., and Manning, W.D., (2022). Teens’ Self-Reported Expectations and Intentions for Marriage, Cohabitation, and Childbearing. (Research Brief). Bethesda, MD: Marriage Strengthening Research and Dissemination Center.