Conceptualizing and Measuring Romantic Relationship Quality in Adulthood

Paul Hemez, Karen Benjamin Guzzo, Susan L. Brown, Wendy D. Manning, and Krista K. Westrick-Payne

Overview

Romantic relationships—which include dating, cohabiting, and marriage—play a central role in many individuals’ lives. Most people experience one or more romantic relationships in their lifetime and many adult households are organized around romantic relationships. Research has established that high-quality, stable romantic relationships are generally linked to increased well-being among individuals, although literature suggests this can vary across age, gender, and type of relationship.1-5

Many romantic relationships result in children, who are also affected by the quality of their parents’ relationships. Although more limited than research on how family structure (e.g., whether parents live together or are married) is associated with child outcomes, research generally shows that children whose parents report better relationship quality tend to experience improved health and well-being throughout their lives relative to their counterparts whose parents have poorer relationship quality.6-10 Research also shows that much of the link between parental relationship quality and children’s health is due to greater parental involvement and supportiveness in higher-quality relationships.6,9,10

Given the importance of healthy relationships for adult and child well-being, many social service programs exist to help adults and couples improve the quality and stability of their current and future relationships. However, while relationship stability is relatively straightforward to understand and measure (e.g., do couples stay together or break up?), relationship quality is much more complex to conceptualize and measure.

This brief summarizes recent peer-reviewed research about the meaning and measurement of adult romantic relationship quality in the United States.a We describe how relationship quality is conceptualized and measured within the literature, including an overview of multiple dimensions of relationship quality. We also review some of the ways relationship quality can vary by relationship type (for instance, whether someone is cohabiting with or married to their partner), parenthood, and gender. Finally, we discuss the implications of this body of work for future research and practice.

Highlights

Conceptualization and measurement of relationship quality

- Researchers use a range of measures to assess relationship quality, such as happiness,

affection, commitment, trust, communication, satisfaction, disagreement, and conflict. - An individual may have different types of experiences in their relationship.

- Individuals within a couple may evaluate the quality of their relationship differently.

Correlates of relationship quality

- In general, married individuals report the highest relationship quality compared with those in cohabiting and dating relationships, although this is partially driven by the fact that those in lower-quality relationships marry their partners less often.

- Individuals with more socioeconomic resources—especially higher levels of education—tend to evaluate their relationship quality more favorably than those with fewer resources.

- Male partners tend to rate their relationships more favorably than female partners.

Implications for future research and practice

- More consistent measurement of relationship quality across surveys would help establish and verify trends across groups and over time.

- Further research is needed on how well existing measures capture aspects of relationship quality across diverse cultures, contexts, and relationship characteristics.

- Better alignment is needed between program content, participant characteristics, and the outcomes examined in evaluations of programs that address healthy relationships.

Methods

The information in this brief is based on a review of professional and scientific journal articles, book chapters, and reports published primarily in or after 2010 that emphasized measurement of relationship quality. Trend data from earlier than 2010 are included where possible. Additionally, some of the studies use data collected prior to 2010. Whenever possible, we highlight studies that use nationally representative data. However, we also include some key qualitative studies, which use smaller samples to achieve a more in-depth and nuanced understanding of relationship quality.

We mention the following data sets in this review, typically by their acronym:

- Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS)

- General Social Survey (GSS)

- National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health)

- National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79)

- National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97)

- National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP)

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID)

- National Survey of Teen Relationships and Intimate Violence (STRiV)

- Supporting Healthy Marriage Project (SHM)

- Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS)

Our review is limited to different-gender relationships due to limited research to date on same-gender relationships using large-scale surveys. Because we review published research studies, information is limited to the foci and definitions used by other researchers.

For detailed information on the types of measures of relationship quality obtained in publicly available surveys—including many of the surveys used in the research reviewed for this brief—see this Relationship Quality Measures Data Tool, which is a web-based, interactive, and searchable catalog of the relationship quality measures available in several large social surveys. This tool is designed to help users identify which publicly available data sources include specific measures of relationship quality, with details about the years in which the questions were asked and the composition of the respondents.

Conceptualization and Measurement of Relationship Quality

The following section describes common dimensions of relationship quality covered in published research using survey data and provides sample questions (from surveys) for each dimension. Within a relationship, individuals can simultaneously report higher values/more positive responses about one dimension of quality and lower values/more negative feelings about other aspects of the relationship. For example, a person may report being happy in their relationship but also report having frequent disagreements with their partner. Thus, relationship quality can be complex and is defined by more than any single dimension summarized below.

Dimensions of relationship quality

Happiness and satisfaction

Relationship happiness or satisfaction are the most common measures of relationship quality, often captured by asking about individuals’ general attitudes toward, or appraisal of, their relationship, with responses provided as a scale. Such measures focus on individuals’ experiences within their relationships rather than their interactions with partners, and researchers sometimes use the terms ‘relationship satisfaction’ and ‘relationship quality’ interchangeably.11

Survey items on relationship satisfaction and happiness often include questions such as:

- How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement about your relationship with [initials]? Overall, you are satisfied with your relationship with [NAME].” (Add Health)

- “In general, would you say that your relationship with [partner] is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” (FFCWS)

- “Using a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 means not satisfied and 7 means very satisfied, how satisfied are you with your (current) relationship in general?” (PSID)

Commitment and trust

Researchers also measure relationship quality through reported levels of commitment and trust. Since there are differences in commitment or levels of trust across types of relationships, questions asked about people in dating relationships may be different, by design, than those asked of married individuals.

Examples of survey questions about commitment include:

- “In many relationships, one person is more ‘into’ the relationship than the other. Would you say you are more into it, [partner] is more into it, or you are about the same?” (FFCWS)

- “How committed would you say you are to [partner], all things considered? Use a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not committed at all and 10 is as committed as possible” (NLSY97)

Questions about trust can also address general feelings about relationships or potential partners (for instance, whether men or women can be trusted), about one’s own relationship overall, or about specific behaviors (e.g., jealousy). For example, respondents may report the extent to which they agree or disagree with statements like:

- “Girls will often use a guy to make another guy jealous.” (TARS)

- “I can rely on my partner to react in a positive way when I expose my weaknesses to him/her.” (Trust Scale).12,13

Sexual fidelity is a key sub-component of trust and commitment, as the majority of couples expect to be sexually exclusive with their romantic partner during the relationship14; however, there is increasing attention by researchers to the prevalence of and people’s familiarity with consensually nonmonogamous relationships.15 Survey questions may tap into both actual extra-relationship (i.e., taking place outside of a relationship with a different partner) sexual experiences or attitudes or concerns about a partner’s faithfulness. Studies on sexual fidelity consider direct questions on extra-relationship sex, as well as attitude measures. Examples of direct questions include:

- “Have you ever had sex with someone other than your husband or wife while you were married?” (GSS)

- “During the time you and [partner] have had a sexual relationship, have you ever had any other sexual partners?” (Add Health)

Attitudinal measures include items such as:

- “I cannot (could not) trust [partner] to be sexually exclusive.” (TARS)

- “Most boys/girls and men/women cannot be trusted.” (STRiV)

Communication

Individuals’ reports of communication with their romantic partner are another way researchers measure relationship quality, as these reports reflect a couple’s effectiveness in resolving conflict within the relationship. Communication measures are also used to indicate individuals’ evaluations of their partner’s empathy, ability to listen, and nonverbal communication skills. Examples of survey questions used to measure communication in relationships include:

- “Thinking about your relationship with [NAME], how strongly do you agree or disagree with the following: We have the communication skills needed to make a relationship work.” (TARS)

- “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement about your relationship with [initials]? My partner [listens/listened] to me when I need someone to talk to.” (Add Health)

Affection

Affection generally refers to the physical and verbal expression of love and care. Survey questions designed to capture affection tend to ask partners whether they feel they express love and care to one another. However, prior studies note that not all couples, or individuals within couples, express affection in the same fashion or to the same extent, suggesting that lower levels of affection are not always indicative of lower relationship quality.16

Examples of survey questions used to capture affection within romantic relationships include:

- “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not close at all and 10 is very close, how close do you feel towards your [spouse/partner]?” (NLSY97)

- “How much do you feel that [your partner] cares about you?” (NLSY97)

- “How much do you love your partner?” or “How much does your partner love you?” (Add Health)

Relationship support

Spousal or partner support is another commonly studied dimension of romantic relationship quality. Support can be conceptualized and measured in a number of ways (e.g., emotional, physical, and co-parenting support) and researchers often either consider one dimension of partner support or combine multiple dimensions through an index or scale. Support from a partner or spouse is an important overall resource for health and well-being.

Examples of survey questions used to capture support include:

- “How often can you rely on [CURRENT PARTNER] for help if you have a problem? Would you say never, hardly ever or rarely, some of the time or often?” (National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project)

- “[Biological father] supports you in the way you want to raise [Child]?” (FFCWS)

Disagreement and conflict

Romantic partners’ reports of disagreement and conflict within a relationship are one of the most direct ways to gauge low relationship quality (i.e., higher conflict corresponds to lower quality). This dimension overlaps partially with how partners communicate in their relationships. Surveys measuring conflict or disagreement within romantic relationships often ask about the source(s) and severity of conflict.

Examples of survey questions that capture disagreement and conflict include:

- “How frequently do you and [spouse/partner’s name] have arguments about: chores and

responsibilities? your children? money? showing each other affection? religion? leisure time? drinking? other men\women? relatives?” (NLSY79) - “Over the course of your relationship with [partner], how would you describe the amount of conflict in your relationship as time went by?” (TARS)

Aggression and intimate partner violence

Perpetrating violence toward, or experiencing violence from, a current or former romantic partner—broadly known as intimate partner violence (IPV)—is an extreme form of relationship conflict. Studies assess IPV through perpetration or victimization, although some respondents report both. IPV can also be defined and measured in a variety of ways (e.g., physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, emotional abuse), making comparisons of the precursors and consequences of IPV difficult across data sets.

Survey questions used to capture IPV include:

- “During this relationship, how often a) has your partner pushed you, hit you, or thrown something at you that could hurt b) have you pushed, hit, or thrown something at your partner that could hurt?” (FFCWS)

- “Thinking of the worst violent incident with [partner]: when did this incident occur? Were either of you physically injured during this incident? Did you go to a doctor?” (TARS)

Perceptions of instability and future outlook

Relationship instability happens when couples divorce or break up, and many relationships with lower quality will eventually dissolve. An indicator of relationship instability among intact relationships, however, might focus on “relationship churning,” where individuals break up and get back together at least once over time. Surveys might also ask respondents about their perceptions of or confidence in their relationships’ future.

Questions that capture these types of relationship instability include:

- “How many times have you two broken-up?” (TARS)

- “Using a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 means ‘Very Unlikely’ and 7 means ‘Very Likely,’ how likely is it that you and your (current) [spouse / partner] will still be together five years from now?” (PSID)

- “Have you ever thought your marriage was in trouble?” (SHM)

Variation in Relationship Quality

Within a relationship, individuals’ and couples’ evaluations of relationship quality may vary by other aspects of the relationship (e.g., whether the relationship is a cohabitation or marriage, whether partners have children together, or whether partners have been married before and/or have children from a prior relationship). There is also variation by factors such as socioeconomic status and finances (such as educational attainment or shared bank accounts); gender; or race, ethnicity, or nativity. These latter factors are also linked to relationship type—specifically, being in a cohabiting or marital relationship—and help to account for variation in relationship quality across relationship types.

Differences between cohabiting and marital relationships

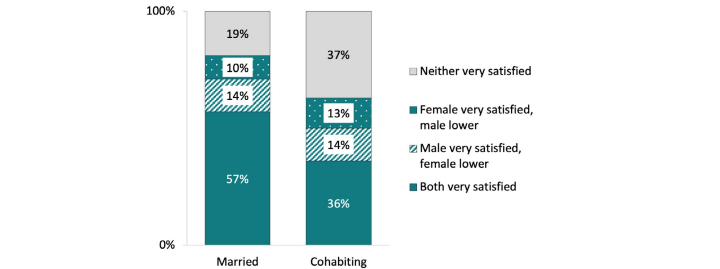

Individuals in marriages tend to have higher relationship quality than those in cohabiting relationships, who in turn have higher relationship quality than those in dating relationships.17,18 For example, jealousy is less often a source of conflict within marriages than in cohabitations, and the likelihood of being sexually exclusive with a romantic partner tends to increase as young adults transition to marriage.19,20 Intimate partner violence, on the other hand, tends to be more common within cohabiting unions than in dating or marital relationships.21 Figure 1 presents an example of the differences in relationship quality between cohabiting and married couples, focusing on relationship satisfaction.22,23

Figure 1. Relationships Satisfaction Among Married and Cohabiting Couples, 2010

Source: Burgoyne, S. (2012). Relationship quality among married and cohabiting couples. Family Profiles, FP-12-12. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ncfmr_family_profiles/127

Couples in marriages more often report that both spouses are very satisfied with their relationship than do partners in cohabiting unions (57% versus 36%). Although relationship quality differs across married vs. cohabiting relationships, being in a marital versus cohabiting union is unlikely to directly determine relationship quality. In fact, couples with the highest relationship quality are most likely to get and stay married, a phenomenon described by social scientists as “selection.” In other words, individuals in the most stable and well-adjusted relationships “select” themselves into more committed and serious relationships—namely, marriage.

In general, relationship quality tends to be relatively stable over time for most married couples.24,25 Only a minority of married couples experience steep declines in marital quality over time, often in response to severe financial distress or other stressful life experiences such as the transition to parenthood (see discussion below). Not surprisingly, couples with declining relationship quality are at greatest risk of divorce. Still, a nontrivial share of couples in marriages characterized as stably happy also get divorced, underscoring that marital quality is not as strong a predictor of divorce as one might imagine. In general, the risk of divorce drops over time, with those in longer marriages much less likely to experience divorce than those who have been married less time. Relative to marriage, cohabiting unions in the United States tend to be rather short, lasting just a year or two before either transitioning to marriage or ending through separation. Recent research shows that, like marriage, the quality of cohabiting unions does not differ by relationship duration.26 Research also indicates that today’s marriages are of comparable quality to marriages in the past. 27

These general trends mask important variation, though, depending on the relationship quality dimension and population being studied.23,28,29 Cohabitation is now widespread in the United States and roughly 40 percent of cohabiting unions transition to marriage.30 The differences we see between married and cohabiting unions raise important questions about whether and how cohabitors’ marital intentions are linked with relationship quality and whether cohabitation itself is tied to marital stability. In general, studies find that cohabitors who have definite plans to marry (such as those who are engaged) report higher levels of relationship quality than those with no such plans, although some studies find few differences in the quality of engaged and non-engaged cohabitors’ relationships when considering specific dimensions of quality or subpopulations.31-33 Moreover, moving in together to spend more time together is linked with better relationship quality (higher commitment and satisfaction, as well as lower conflict), whereas moving in together as a way to test the relationship has been linked with worse quality.26 Among couples who married prior to the 1990s, living with a future spouse before marriage was tied to an increased likelihood of divorce.34,35 However, while some debate remains, more recent literature largely suggests that the positive association between premarital cohabitation and divorce is no longer evident for couples who wed after the mid-1990s, although married couples who cohabited before marriage report lower levels of relationship happiness than those who married without cohabiting first.31,35-40

Parenthood

In general, couples’ transition to parenthood is associated with a decline in relationship satisfaction, with couples who reported higher levels of marital satisfaction before having a child experiencing larger declines in marital satisfaction than couples with lower levels of pre-parenthood satisfaction.41 Among parents, though, fathers’ engagement with children and higher levels of co-parenting (parental engagement from both partners) are positively associated with relationship quality; however, current parental engagement does not necessarily predict relationship quality in the future.7,29,42

Remarriages and stepfamilies

There are mixed findings regarding whether past relationship experiences (such as a previous marriage or children from a previous relationship) influence the quality of one’s current romantic relationship. Some studies find that individuals in first marriages agree about marital issues more regularly, work harder to maintain a strong relationship, express fewer positive attitudes toward divorce, and are less prone to experiencing a marital dissolution than those in remarriages.43-45 At the same time, research shows that spouses in first marriages report the same levels of marital conflict and happiness as those who are remarried.45 Remarriages involving children from prior relationships add additional considerations. Scholars argue that effective communication, support, and compromise are especially important for individuals navigating the challenges related to being in a stepfamily.45

Socioeconomic status

Some measures of socioeconomic status (SES), such as education attainment, are associated with better relationship quality, whereas other indicators, such as income, are less clearly related.b More highly educated cohabitors, for example, report spending more time together and are more likely to express plans to marry than their counterparts with less education. However, there is little evidence that educational attainment is associated with other dimensions of cohabitors’ relationship quality such as feelings of happiness and fairness and perceptions of disagreement and arguing.46

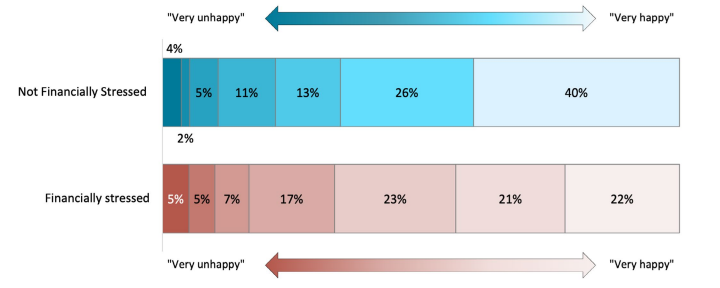

Perceptions of financial circumstances and management appear to be more closely tied to relationship quality than more general measures of SES (such as educational attainment), as economic strains can directly lead to conflict and stress. Adults who feel they practice sound financial management, for example, report higher levels of relationship happiness.47 Figure 2 displays the association between financial stressors and relationship happiness for marital and cohabiting couples. Generally, couples who were financially distressed report lower levels of relationship happiness than those who did not report financial burdens.48-50 Given the stark socioeconomic differences in cohabiting and married couples, the positive link between SES and relationship quality often explains differences in quality of relationships across different union types.23 In other words, married couples may report higher relationship quality than cohabitors because they experience fewer economic stressors.

Figure 2. Relationship Happiness by Financial Stress Among Coresidential Couples

Source: Payne, K. K. (2011). Families and Households: Economic Wellbeing (FP-11-01). National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-11-01.pdf

Trust and commitment can be indicated by certain behaviors among couples, such as whether they hold joint bank accounts and/or have a shared understanding of financial circumstances. In turn, financial integration (i.e., resource pooling or combining financial resources) is linked with higher relationship quality. Couples with a joint bank account, for example, report better relationship satisfaction, conflict resolution, and overall relationship quality on multidimensional scales than those with separate accounts.33,51 Furthermore, cohabiting couples who share a mortgage are more likely to transition to marriage.52 Shared financial responsibilities can denote a partner’s confidence in the relationship and some literature finds that levels of commitment are greater for cohabitors who integrate their finances than for married spouses with integrated finances.51 However, it is important to note the reciprocal nature of the relationship between couple’s financial management and their relationship quality. One study, for example, finds that better relationship satisfaction resulted in better financial management practices among husbands.53

Intimate partner violence, or IPV, is strongly associated with SES. In general, economic hardships are associated with increased levels of violent or controlling behaviors within romantic relationships.54,55 The degree or severity of IPV can also vary across SES. Among those who had recently left a relationship in which IPV occurred, those who experienced the most extreme abuse histories were more often unemployed, had a lower income, and received social benefits more often than those with the shortest abuse histories.56 Again, though, causal conclusions should be drawn cautiously: It is likely the case that individuals with more economic resources are able to leave abusive relationships sooner because they are less financially dependent on their partner.

There is mixed evidence regarding the relationship between SES and sexual exclusivity.57 Specifically, some literature finds the likelihood of sexual exclusivity is greater among those with more years of education,58 whereas others find no link between various indicators of SES and the chances of remaining sexually exclusive in their romantic relationships, at least among young adults.59,60

Gender

More than 50 years ago, sociologist Jessie Bernard wrote that any given marriage actually consists of two marriages: “his” marriage and “her” marriage.61 That is, gender influences how individuals experience a romantic relationship given power imbalances at both the interpersonal and societal levels. Husbands, on average, report better relationship quality than their wives.62 Among cohabiting women, having plans to marry is associated with greater relationship happiness (relative to those who directly married without cohabiting), an association that is not observed among men.31 Furthermore, within cohabiting and marital relationships, women whose partner has poor physical health report more conflict, but this is not the case for men.63 Relationship quality can be particularly important at older ages, when spouses or romantic partners act as the primary caregivers to those with physical or cognitive limitations. Some research suggests that, among adults in later life, married women experience lower levels of happiness and support than married men, likely reflecting women’s much higher propensity to act as a caregiver to their spouse.64

Within marriages, the relationship between socioeconomic status and marital quality can also depend on gender differences in household financial or other contributions. Making more money than one’s spouse tends to be associated with lower marital quality among women but higher marital quality for men.65 Similarly, husbands’ lack of full-time employment is linked with increased chances of divorce, whereas wives’ employment status does not appear to be associated with marital stability.66 Perceived unfairness in the division of labor within the household—or the amount of time spent on household chores—is linked with relationship quality among women, but not among men.67

Identifying these gender differences requires dyadic data, where both partners are asked about their perceptions of the relationship. These responses can be combined to study patterns of disagreement and inconsistency, to create joint measures of relationship quality, or to examine whether having couple-level data can improve the predictive power of relationship quality for subsequent outcomes.68 This is an important approach, since research finds that dimensions of relationship quality (such as satisfaction or conflict) are often only moderately correlated between partners and can depend on both a respondent’s individual characteristics and perceptions as well as those of their partner.69-71 For instance, when men underestimate the amount of work-family conflict their partner feels, they tend to report higher relationship quality. However, the opposite is true among women, such that women who underestimate their partner’s perceived work-family conflict express worse relationship quality.72 Overall, using information at the couple level allows researchers to achieve a more nuanced understanding of relationship quality and the factors that can influence how partners perceive and experience the relationship.

Race, ethnicity, and nativity

There is a growing recognition in family science and other fields of family research of systemic racism and differential lived experiences among groups of people with different racial and ethnic identities, nationalities, and immigration status. This recognition and focus on different lived experience is mirrored in a small but growing body of research on differences in relationship quality across groups,73,74 as well as in research that focuses exclusively on a single race or ethnic group.75-77 Much of the literature in this latter category uses smaller samples or qualitative research designs because large data sets typically have small numbers of respondents from specific racial or ethnic groups, precluding group-specific studies. Some of this work considers variation across groups in key characteristics linked to relationship quality (e.g., SES, cohabitation experience, the presence of children from prior unions),73 while other work focuses on how experiences of discrimination and adversity are associated with relationship quality.78,79 Still, considering the well-documented differences in union formation and dissolution across racial and ethnic groups, there is surprisingly little research that explores the individual- and couple-level processes in play for multiracial individuals and for individuals partnered with individuals of a different race or ethnicity, nor is there a deep body of work on how cultural beliefs or experiences of discrimination affect relationship processes.80

There are some differences in dimensions of relationship quality across race, ethnicity, and nativity. In general, White individuals in couples report better relationship quality than their Black counterparts, with differences narrowing as relationship duration increases.73,74 There is relatively little work that includes coupled Asian individuals due to sample size issues, but the existing work suggests they do not differ in relationship quality from White individuals in terms of affection and satisfaction.81

Interracial/interethnic couples tend to have poorer relationship quality than couples in same-race/same-ethnicity relationships.82 Findings about the differences in relationship quality between Hispanic individuals/couples and other groups are more mixed: Some research finds little variation83 while other research suggests that coupled Hispanic individuals report poorer relationship quality than their White counterparts, but better than among coupled Black individuals.73 Perry (2016) found that affection was lower among married Hispanic individuals than among their White counterparts, but that overall marital satisfaction did not differ.81 Some of these patterns may be an artifact of variation in marriage and—to a lesser extent—cohabitation rates by race or ethnicity, as well as racial or ethnic differences in the stability of marriages and

cohabiting unions.

Another component to studying race and ethnicity and relationship quality is the need to consider nativity. Immigrant families face unique issues,84 especially when couples experience periods of separation that can be a strain on their relationships and/or their individual well-being.85,86 The legal status of individuals within a couple can also negatively impact relationship quality, whether through direct concerns about deportations, the indirect effects on employment and living conditions, or—in the case of mixed-status relationships—doubts about whether one’s partner was interested in them for love or for the possibility of attaining legal status through marriage.87 Additionally, acculturation issues can be another source of conflict, particularly regarding differences in gender roles between countries of origin and the United States.75,88,89

Implications for Research and Practice

Implications for research

Although much research over previous decades has focused on understanding the causes and implications of romantic relationship quality, future research should address remaining—and important—gaps and challenges with the literature. First, the numerous dimensions of relationship quality and the various ways to conceptualize these dimensions are not consistent across the literature. For instance, questions in any given survey may not correspond to questions in other surveys, or even to earlier waves of data collection for longitudinal projects.c Such inconsistencies are problematic for establishing and verifying trends across groups or over time. Future research and study designs should use similar questions and constructs to make the replication or updating of findings more feasible.

Future research should also consider examining whether the correlates of relationship quality vary across relationship types. This brief has not extensively discussed work that directly compares whether various characteristics (e.g., income, gender, age, race/ethnicity/nativity) affect relationship quality in similar ways for different types of relationships, because many studies of relationship quality do not test this. Other work focuses on a single relationship type, precluding comparisons across groups. Similarly, there is growing recognition that existing measures may not capture aspects of relationship quality equally well across cultures, contexts, and other characteristics. For instance, research suggests that relationship quality scales designed to measure satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, and trust do not measure these concepts equally well in samples from different countries,90 limiting researchers’ ability to use a standard set of measures to make comparisons. Attention to whether such measures do, or do not, capture salient aspects of relationship quality across groups within the United States—such as across gender, race/ethnicity, or country of origin—is also important given the comparative framework of many studies. Alternatively, such findings also suggest that comparisons may not always be appropriate or necessary: A comparative framework often sets a particular group (usually a socially privileged group) as the standard and, explicitly or implicitly, adopts a deficit approach to documenting differences.

Re searchers also have an opportunity to consider additional topics within the relationship quality literature, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, incarceration, or work-family balance. The limited data available on same-gender couples precluded a review of relationship quality among these couples in this brief, although the legalization of same-gender marriage in 2015 should allow new avenues of research that further our understanding of romantic relationships in the United States. Researchers must be cognizant, however, of the ways in which they formulate research questions and design studies. Researchers have critiqued work on race/ethnicity/nativity, for instance, emphasizing that a deficit perspective—in which middle-class White, heterosexual marital relationships are set as the standard—ignores the complex interplays of race, class, and gender identity that affect intimate partnerships.91-93 The same is likely true for work addressing other types of marginalization, including around sexual orientation and gender identity.

Finally, since perceptions of relationship quality may not remain constant over time, longitudinal surveys that collect information from both partners are most appropriate for examining the correlates, predictors, and consequences of relationship quality throughout the life course. Moreover, future studies on these trajectories must pay attention to the nuances of the timing, characteristics, and previous experiences of partners when examining the well-being of relationships.

Implications for practice

Healthy marriage and relationship education (HMRE) programs aim to support and promote the quality and stability of romantic relationships by helping individuals and couples develop key relationship skills. One implication of the relationship quality literature synthesized in this brief is that HMRE programming has the potential to support or improve upon the many dimensions of relationship quality we’ve identified. However, a recent Marriage Strengthening Research and Dissemination Center (MAST Center) brief revealed that the majority of HMRE curricula focus on a more limited set of skills, including conflict management and communication skills,94 while research on relationship quality encompasses a broader range of indicators that include commitment, support, and general happiness within relationships. Although these dimensions

are intertwined, HMRE programs may be more beneficial for couples if they address a broader range of relationship quality dimensions within their curricula. Evaluators of HMRE programs should also consider whether the outcomes examined to determine program success capture the range of possible dimensions of relationship quality. A recent review of the types of outcomes measured in evaluations of HMRE programs found that relationship quality outcomes consisted of measures of relationship satisfaction, intimate partner violence, and commitment to and confidence in the relationship.95 Importantly, these measures go beyond examining relationship status alone (i.e., whether couples stayed together), but future HMRE program evaluation should consider additional domains of relationship quality, depending on what is addressed in the specific curricula delivered and on who participates in the program. Using the Relationship

Quality Measures Data Tool, HMRE practitioners and evaluators can draw on the range of existing data sets that measure multiple dimensions of relationship quality to identify the best ways to ask questions about relationship quality.

Finally, although many HMRE programs are designed to serve a specific priority population (e.g., couples with low incomes, parents), families in the United States who belong to these priority populations are otherwise diverse.96 HMRE programs and practitioners and researchers that evaluate these programs should be cognizant of how the dimensions of relationship quality—as well as their correlates and effects—may vary across groups and even within couples.