Centering Positive Youth Development to Enhance Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education Programming

Asari Offiong, Desiree W. Murray, Mindy E. Scott, Lindsay Anderson, Deja Logan

Overview

Adolescence is an ideal time to help youth develop healthy relationship skills that support their lifelong health and well-being.1 Adolescents are developing a sense of personal and socio-cultural identity, they are curious about new experiences, they seek greater autonomy and agency, and they are increasingly connected to their peers. These changes create opportunities for learning and developing skills that can influence lifelong relationship experiences in many contexts. Indeed, healthy relationship skills—such as the ability to communicate and collaborate with others and manage conflict—have been shown to promote social and emotional health, including perceptions of self-worth, goal achievement, and success in the workplace.2-7

Several state and federal initiatives focus on healthy marriage, and relationship education (HMRE) for youth. However, such programs have not traditionally considered the unique developmental needs of youth (e.g., identity development, heightened curiosity and exploration, need for independence, and interpersonal bonding) in their design and delivery,8 demonstrating the benefits of a youth-specific framework.

This brief describes the potential benefits of integrating Positive Youth Development (PYD)—a developmental framework that focuses on youth’s assets and strengths—into HMRE programming to inform the work of HMRE program directors and administrators, as well as the efforts of educators, employers, and a range of youth-serving staff. We first describe HMRE programming for youth. Then, we introduce PYD and link its key principles to programmatic strategies focused on recruitment and retention, curriculum content and delivery, staff facilitation, and evaluation. We encourage HMRE program directors, administrators, and facilitators to review the PYD informed strategies in this brief and consider implementing them in their programming for youth.

Key Takeaways

- In recent years, HMRE program funders, developers, and providers have increasingly designed and implemented HMRE programming for youth.

- HMRE programs that focus on youth face design and implementation challenges related to youth engagement and whether their content is age-appropriate, developmentally appropriate, and culturally responsive.

- PYD has six principles that may be leveraged for HMRE programming, building on the key developmental features of adolescence: (1) intentionally teach prosocial skills; (2) build strong relationships between youth and adults; (3) recognize, draw on, and enhance youth strengths; (4) respond to youth’s specific needs, vulnerabilities, and preferences; (5) leverage family and community assets; and (6) create opportunities for meaningful youth engagement.

- The PYD framework may be applied to develop clear strategies to address design and implementation challenges and enhance the impact of HMRE programming for youth.

HMRE Programming for Youth

Although research and federal policy have come to prioritize HMRE programming for youth, there has historically been limited attention by funders or providers to tailoring program content and activities to youth’s developmental and cultural needs.8,9 In 2020, for the first time, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the United States Department of Health and Human Services allocated funding to provide HMRE programming specifically focused on youth, to be delivered in both schools and community-based settings.10 For the purposes of federal HMRE programming, youth are typically defined as high school-aged adolescents and young adults up to age 24.8 Youth-focused HMRE programming strives to enhance youth’s attitudes and expectations concerning romantic relationships; help them develop important skills for forming healthy relationships with romantic partners, peers, and parents and caregivers, and foster other interpersonal relationships; and avoid unhealthy relationships that may lead to intimate partner violence or other negative outcomes.8

HMRE programming has typically focused on skills such as communication and problem-solving (or conflict resolution).11 However, research also suggests the potential value in targeting other skills like self-regulation.a,12,13 This enhanced focus was recently addressed in a project called Self-Regulation Training Approaches and Resources to Improve Staff Capacity for Implementing Healthy Marriage Programs for Youth (SARHM). SARHM trained HMRE facilitators to provide co-regulation, an interactional process that involves developing warm, responsive relationships; creating safe, supportive environments; and coaching self-regulation skills through day-to-day interactions.14 The SARHM project demonstrated the promise of this enhanced approach for addressing some of the specific challenges around youth engagement and program facilitation in HMRE programs.15

With regard to outcomes, HMRE programming has shown evidence of enhancing youth’s abilities to foster, navigate, and maintain healthy relationships. A meta-analysis of 30 HMRE programs for youth and young adults found moderately strong short-term positive effects of HMRE programming on youth’s self-reported relationship attitudes and skills.1 Findings suggesting greater benefit for youth from lower-income backgrounds—a priority population for many HMRE programs—were particularly encouraging. However, effects appeared to be smaller for adolescents younger than age 18 than for young adults ages 18 to 29, and few studies evaluated the longer-term impacts of HMRE programming. Overall, while HMRE youth programming is promising, there is significant room to enhance such offerings to ensure that programs achieve their broad goals.

Program implementation challenges are, in part, why HMRE youth programming has opportunities to improve. Based on a summary from a Technical Work Group convened by ACF to discuss HMR programs for youth, HMRE programs struggled to identify and connect relevant topics to youth experiences16-18—for example, making relationship education content feel relevant for youth who have not been in romantic relationships. Other implementation concerns include a need for more activities to engage male participants, strategies to address behavioral issues, and staff training on delivering culturally appropriate programs.

Given that HMRE programming has not specifically focused on youth until recently, there is limited guidance and few examples of how to integrate key features of adolescence development into HMRE programming.19-21

Informing HMRE Program Strategies with Positive Youth Development Principles

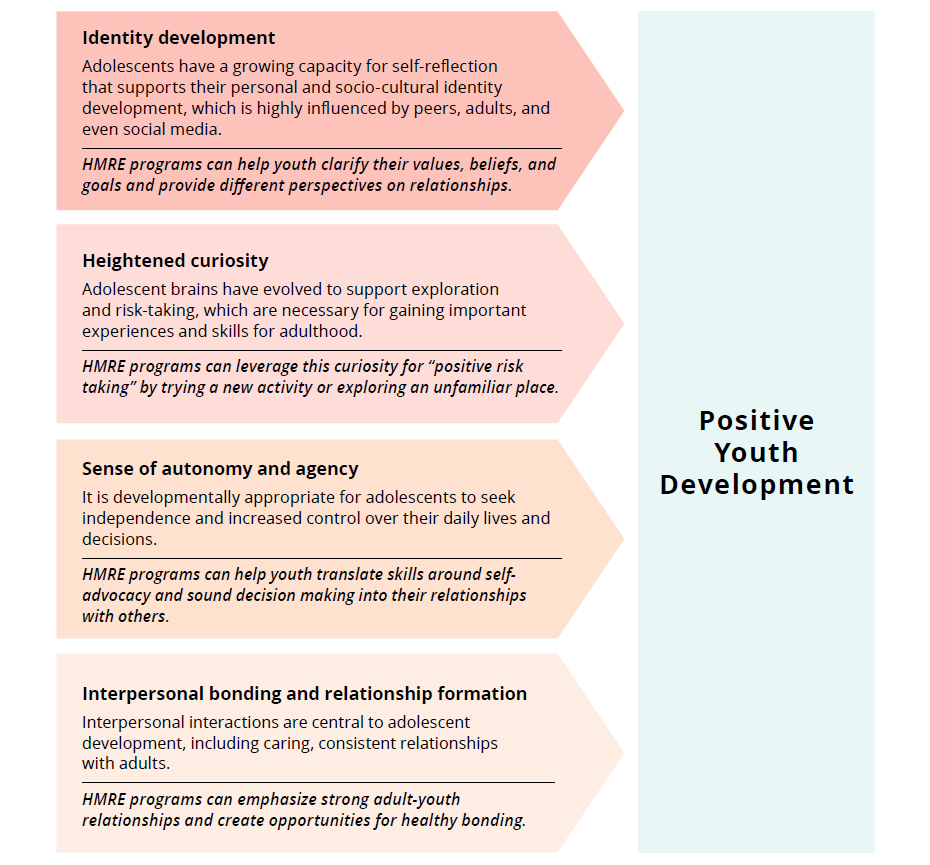

Positive Youth Development is a framework that highlights youth’s individual assets and strengths—along with the many environments and systems in which they interact—to promote positive outcomes and engage youth in prosocial skill building.22,23 It is an evidence-based approach that builds on the key developmental features of adolescence (including identity, curiosity, autonomy and agency, and interpersonal bonding and relationship formation; see Figure 1). It is also well-grounded in relationship theory, which aligns with the co-regulation model described in SARHM. The principles of PYD (summarized below) also serve as a framework to understand how youth programs can engage, influence, and positively impact young people’s lives.

Positive Youth Development (PYD) overview

PYD is an intentional, prosocial framework that:

- Engages youth within their communities, schools, organizations, peer groups, and families in a manner that is productive and constructive.

- Promotes positive outcomes for young people by providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships, and furnishing the support needed to build on their personal strengths.

Source: Positive Youth Development from the Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs

Figure 1. Key Developmental Features of Adolescence

To optimize HMRE Programming for young people, key developmental features of adolescence that drive positive youth development should be considered. In italics are specific ways these features can be connected to and are relevant for HMRE programming.

Six Principles of PYD

- Take an intentional approach to teaching prosocial skills. PYD proactively identifies positive and health-promoting behaviors among youth.

- Build strong relationships between youth and adults. PYD emphasizes the important role that adults play in youth’s lives, while also recognizing the value of youth’s voice, thoughts, and emotions.

- Recognize, draw on, and enhance youth strengths. PYD builds on the premise that all youth have talents, gifts, and ideas to contribute, and that those strengths should be the focus of all interactions and programming.

- Respond to the specific needs, vulnerabilities, and preferences of youth, including those that relate to a youth’s culture. PYD considers the unique experiences of youth, who often have a variety of backgrounds and identities that shape who they are and their experiences in the world.

- Leverage assets from families and communities to build supports for youth. PYD recognizes that youth are heavily influenced by their social contexts, so their family and community assets help sustain program impacts on their decisions, behaviors, and outcomes.

- Create opportunities for meaningful youth engagement. PYD promotes civic engagement and leadership opportunities, viewing youth as valuable partners in addressing issues that concern their health personally and their community at large.

The PYD framework can inform the design and implementation of HMRE programming in several ways to better support the developmental needs of young people and, potentially, improve their HMRE outcomes. In a recent review of youth HMRE programs, Scott et al. made several recommendations, including increasing opportunities for youth leadership; breaking complex concepts into simpler ideas; providing opportunities for youth to practice skills during program lessons; and making connections between the lesson, real-world circumstances, and youth’s personal lives.8 This review also suggested that HMRE program staff need more knowledge and training in applying these strategies.8 A first step in this direction would be to incorporate the SARHM project’s focus on co-regulation (described earlier), which includes strategies for curriculum content, delivery, and facilitation.24

In the table below, we summarize strategies aligned with PYD principles—including those piloted in the SARHM project—for various stages in HMRE programming, including recruitment and retention, curriculum content and delivery, facilitation, and evaluation.

Table 1. Strategies for HMRE Design and Implementation Using PYD Principlesb

| HMRE Design and Implementation Stages | Relevant PYD Principles | Recommended Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment and retention | Leverage assets from families and communities to build supports for youth. |

|

| Curriculum content | Create opportunities for meaningful youth engagement.

Recognize youth strengths. Respond to youth needs, vulnerabilities, and |

|

| Curriculum delivery | Use an intentional skill-building approach.

Recognize youth strengths. |

|

| Facilitation | Build strong relationships.

Respond to youth needs, vulnerabilities, and preferences. |

|

| Evaluation | Respond to youth needs, vulnerabilities, and preferences. |

|

Conclusion

Given the importance of relationship skills for youth’s long-term developmental outcomes, efforts to develop and implement effective youth-focused HMRE programs are critical. A PYD framework has strong potential to advance this goal by informing HMRE program implementation strategies, such as those identified in the SARHM pilot project. PYD’s emphasis on youth’s assets and honoring their lived experiences may further strengthen youth engagement and enhance program success.25-27 To achieve this potential, HMRE staff will need training in PYD and co-regulation. PYD can also be used to design new HMRE programs, such as Be CALM Connections, a mindfulness-based relationship education program that trains high school teachers in co-regulation. Finally, HMRE program evaluation can use a PYD framework to be more responsive to youth preferences and needs. Future evaluation research should consider testing these strategies through rigorous process and impact evaluations. Allocating time and resources to these efforts will build the evidence for the benefits of integrating PYD into HMRE programming for youth.

Footnotes

a Self-regulation refers to the ways in which people coordinate thoughts, feeling, and behaviors to reach their goals; it includes skills like impulse control, managing stress and anger, decision making, and problem-solving.15

b Strategies included in this table are informed by the development of the Be CALM Connections program, funded by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Grant: 90ZD0023-01-00; and the Self-Regulation Training Approaches and Resources to Improve Staff Capacity for Implementing Healthy Marriage Programs for Youth (SARHM) project (Contract number HHSP233201500114I / HHSP23337002T).